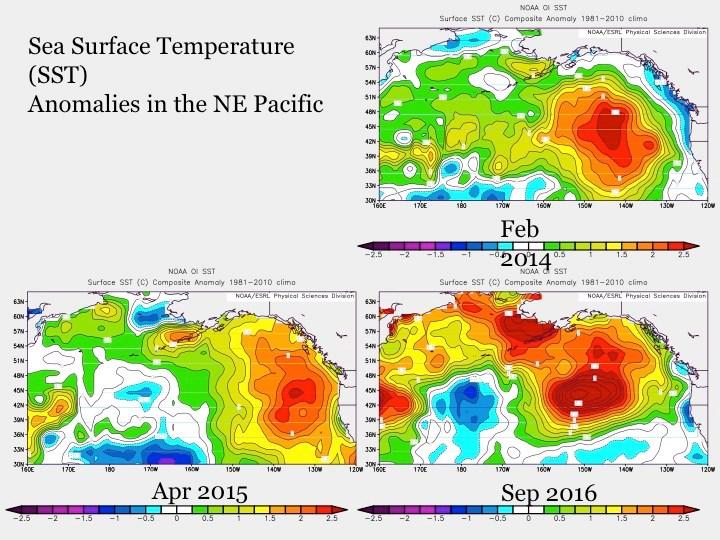

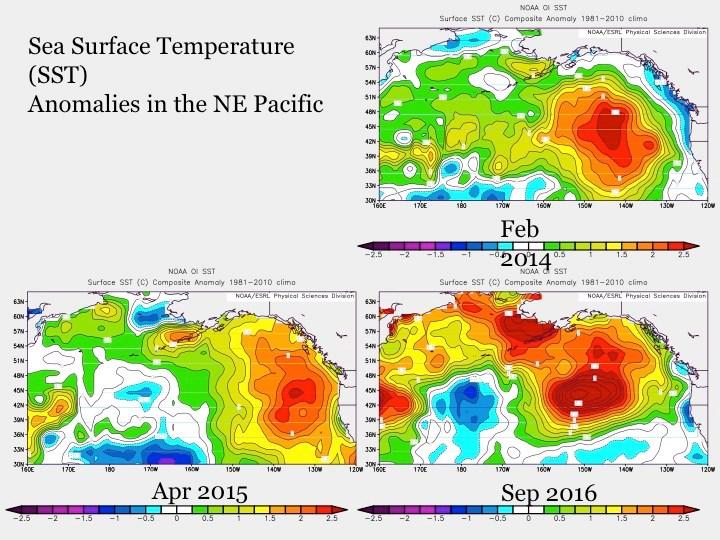

- Early 2014: the Blob’s movement from the open ocean to the west coast,

- Late 2014: intensification of unusually warm temperatures along the west coast, driven largely by winds,

- Mid-2015: a wind-driven upwelling event that cooled things off briefly until warm conditions returned, and

- Early 2016: an El Niño event that enhanced warming.

The research team found that of these stages, both the beginning and end were predictable but the wind-driven middle stages were less predictable. “When wind-driven changes are associated with a strong El Niño or La Niña event, they are more predictable. However, when there isn’t a strong ENSO event, winds can still drive temperature changes but they tend to be unpredictable,” explained Jacox. Along with figuring out which parts of the heatwave’s evolution were most predictable, the researchers also looked at a large ensemble of model forecasts to see how many of them predicted the occurrence of a marine heatwave. Looking at the outputs from 85 forecasts in the North American Multi-Model Ensemble (NMME), a U.S.-Canadian seasonal forecasting system that was spearheaded by NOAA’s Climate Program Office Modeling, Analysis, Predictions and Projections program with many partners, the scientists saw that the models still indicated increased likelihood of a marine heatwave even when the models didn’t predict the wind-driven events well on average. The authors note that these results are important for potentially establishing an advanced marine heatwave warning system. A system like that would give communities time to prepare for the heatwave in advance, potentially minimizing economic and environmental impacts. “We are entering an era of rapid change and coastal communities need tools to facilitate the development of adaptation policies and strategies,” said Desiree Tommasi, co-author of the study and Project Scientist in the Fisheries Resources Division at NOAA’s Southwest Fisheries Science Center. “Global climate forecast systems being developed by NOAA and other agencies can help provide an early warning system for extreme events, which would allow regional stakeholders to establish timely response measures.” Looking to the future While trying to better understand marine heatwaves, what causes them, how they evolve, and if we can predict them, Jacox said it’s important to think about marine heatwaves in the context of climate change. “I think it’s worth recognizing that there have always been marine heatwaves that last for a year or two years, and they come and go,” he said. “But on top of that, it’s important to think of this kind of study on marine heatwaves in the context of climate change, and how marine heatwaves and long-term ocean warming can both impact the ocean.” Whether marine heatwaves will become worse or more frequent with climate change, however, is a complex question. “We are confident there will be a warming trend but what’s less clear is changes in heatwaves. Whether the heatwaves themselves will become more frequent or intense is likely to depend on the region.” Jacox recently addressed marine heatwaves and climate change in a short Nature article that provides more in-depth thoughts on the subject. This research is a contribution of NOAA’s Marine Prediction Task Force and is co-funded by NOAA Research’s Modeling, Analysis, Predictions, and Projections (MAPP) Program and NOAA Fisheries’ Office of Science and Technology.