As human-caused climate change disrupts weather patterns around the world, one overarching question is the subject of increased scientific focus: how it will affect one of the world’s dominant weather-makers?

The future of the El Niño Southern Oscillation, or ENSO, is the subject of a new book published by the American Geophysical Union. With 21 chapters written by 98 authors from 58 research institutions in 16 countries, the volume covers the latest theories, models, and observations, and explores the challenges of forecasting El Niño and La Niña. The book, El Niño Southern Oscillation in a Changing Climate, was published online on November 2. Research funded by the Climate Program Office’s Climate Observations and Monitoring (COM) program is included in Chapter 5 while research supported by the Climate Variability & Predictability (CVP) program contributes to Chapter 7.

A giant weather-maker

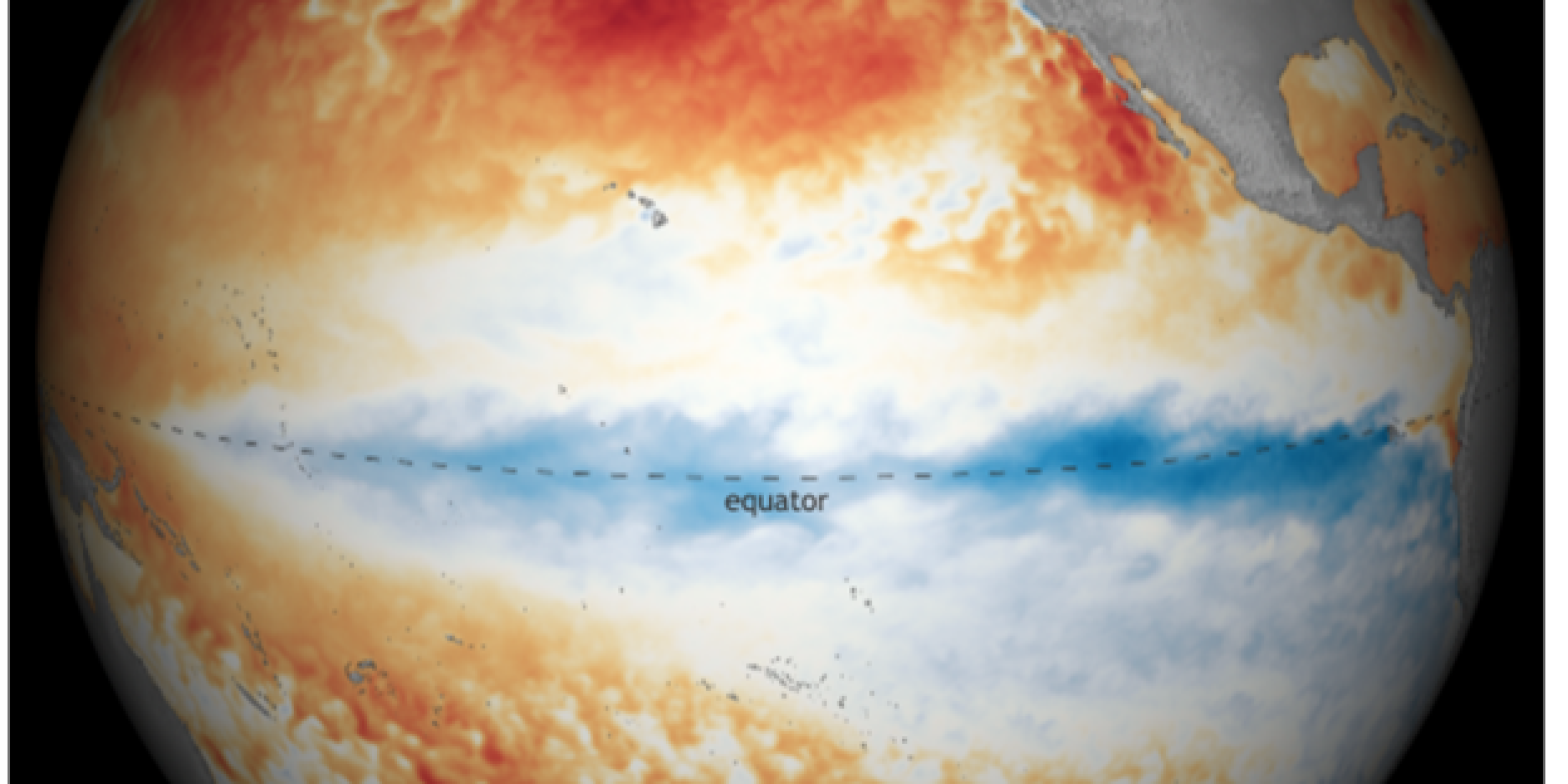

ENSO is a cycle of warm El Niño and cool La Niña episodes that happen every few years in the tropical Pacific Ocean. It is the most dramatic year-to-year variation of the Earth’s climate system, affecting agriculture, public health, freshwater availability, power generation, and economic activity in the United States and around the globe.

“This is the first comprehensive examination of how ENSO, its dynamics and its impacts may change under the influence of rising greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere,” said Michael McPhaden, Senior Scientist with NOAA’s Pacific Marine Environmental Laboratory in Seattle and co-editor of the new volume. Two other co-editors are from Australia: Agus Santoso, a scientist with the University of New South Wales, and Wenju Cai, a researcher with the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, also known as CSIRO.

ENSO impacts around the globe

During El Niño, chances for drought increase across India, Indonesia and Australia and a large part of the Amazon, while the southern U.S. tends to see more precipitation. During La Niña, the pattern is effectively reversed, with wetter conditions for Indonesia, Australia and parts of the Amazon, and dry conditions in the southern tier of the U.S. In September, NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center announced that a La Niña had developed in the Pacific and was likely to last through the Northern Hemisphere winter.

The new book, three years in the making, tracks the historical development of ideas about ENSO, explores underlying physical processes and reveals the latest science on how ENSO responds to external factors such as climate phenomena outside the tropical Pacific, volcanic eruptions, and anthropogenic greenhouse gas forcing.

Chapter 5, “Past ENSO Variability: Reconstructions, Models, and Implications,” synthesizes studies using paleoclimate data to characterize ENSO in eras before instrumentation was available. For example, the Quaternary Ice Ages or the Holocene. In sum, there is a record of ENSO from around at least three million years ago and variations in ENSO behavior are sensitive to large changes in mean climate. The authors consider the pros and cons of using paleoclimate observations and conclude with comments on how to use these observations to improve ENSO representation in climate models.

Chapter 7, “ENSO Irregularity and Asymmetry” summarizes the various processes and effects responsible for the spatial and temporal irregularity and asymmetry of ENSO. In other words, why El Niño and La Niña are not periodic, appear in differing strengths, last differing amounts of time, and exhibit different behaviors over time. The authors find that there are still improvements to be made for most state-of-the-art models with regards to simulating ENSO asymmetry.

Variability a challenge for forecasts

Antonietta Capotondi, a CIRES scientist working at NOAA’s Physical Sciences Laboratory, said in recent decades, scientists have come to appreciate how significantly ENSO impacts can vary from event to event.

“No two El Niños or La Niñas are perfectly alike,” Capotondi said. “We’ve seen how diverse ENSO events can be. This diversity adds another degree of complexity for understanding how climate change will influence future ENSO events.”

So how are ENSO impacts likely to evolve in the coming decades?

“Extreme El Niño and La Niña events may increase in frequency from about one every 20 years to one every 10 years by the end of the 21st century under aggressive greenhouse gas emission scenarios,” McPhaden said. “The strongest events may also become even stronger than they are today.”

In a warming climate, rainfall extremes are projected to shift eastward along the equator in the Pacific Ocean during El Niño events and westward during extreme La Niña events. Less clear is the potential evolution of rainfall patterns in the mid-latitudes, but extremes may be more pronounced if strong El Niños and La Niñas increase in frequency and amplitude, he said.

Some ENSO impacts are already being amplified, such as the extensive coral bleaching and increases in tropical Pacific storm activity observed during the 2015-16 El Niño. ENSO is expected to impact tropical cyclone genesis in the future as it does today in the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans, but precisely how is still an open question.

To learn more about El Nino and La Nina, visit http://www.climate.gov/enso.

This story was adapted from a release written for NOAA Research News. For more information, please refer to the original article.