“I was ten years old back when there was the terrible drought of 1988, and I just remember it being so hot all of the time,” recalls Otkin. “I don’t think I was quite aware yet of what that meant to my parents, but I was still aware that they were worried.”

Forming a relationship with drought

During those foundational years, he grew eager to learn about the weather and climate, and how he could control it to to protect his family’s livelihood. It was a personal relationship with drought that drove him into a career where he could help his parents and other farmers like them.

Otkin’s admiration for the weather and climate took him into an eventual career as Associate Scientist at the NOAA Cooperative Institute for Meteorological Satellite Studies (CIMSS) at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. He now knows no one can control the weather, but he works to help farmers and ranchers reduce their vulnerability to weather and climate impacts with products that provide early warning of drought.

Otkin has been working with other researchers to develop an early warning system for flash droughts. Those droughts reach their peak severity within a matter of weeks, whereas typical droughts usually take several months or even years to reach their maximum intensity and extent. Flash droughts are especially devastating to ranchers and farmers, who have less time to respond to their rapid onset.

Predicting flash droughts

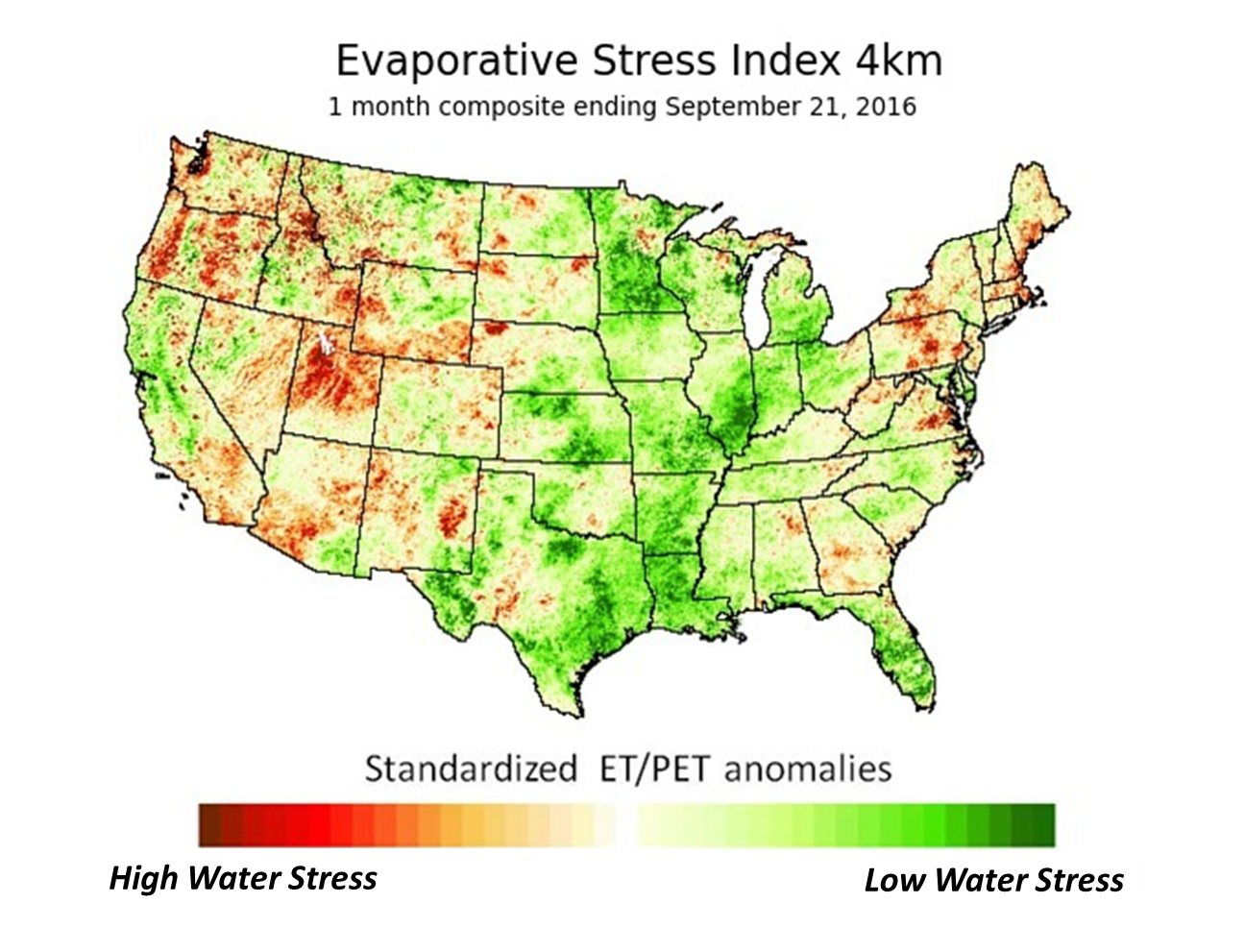

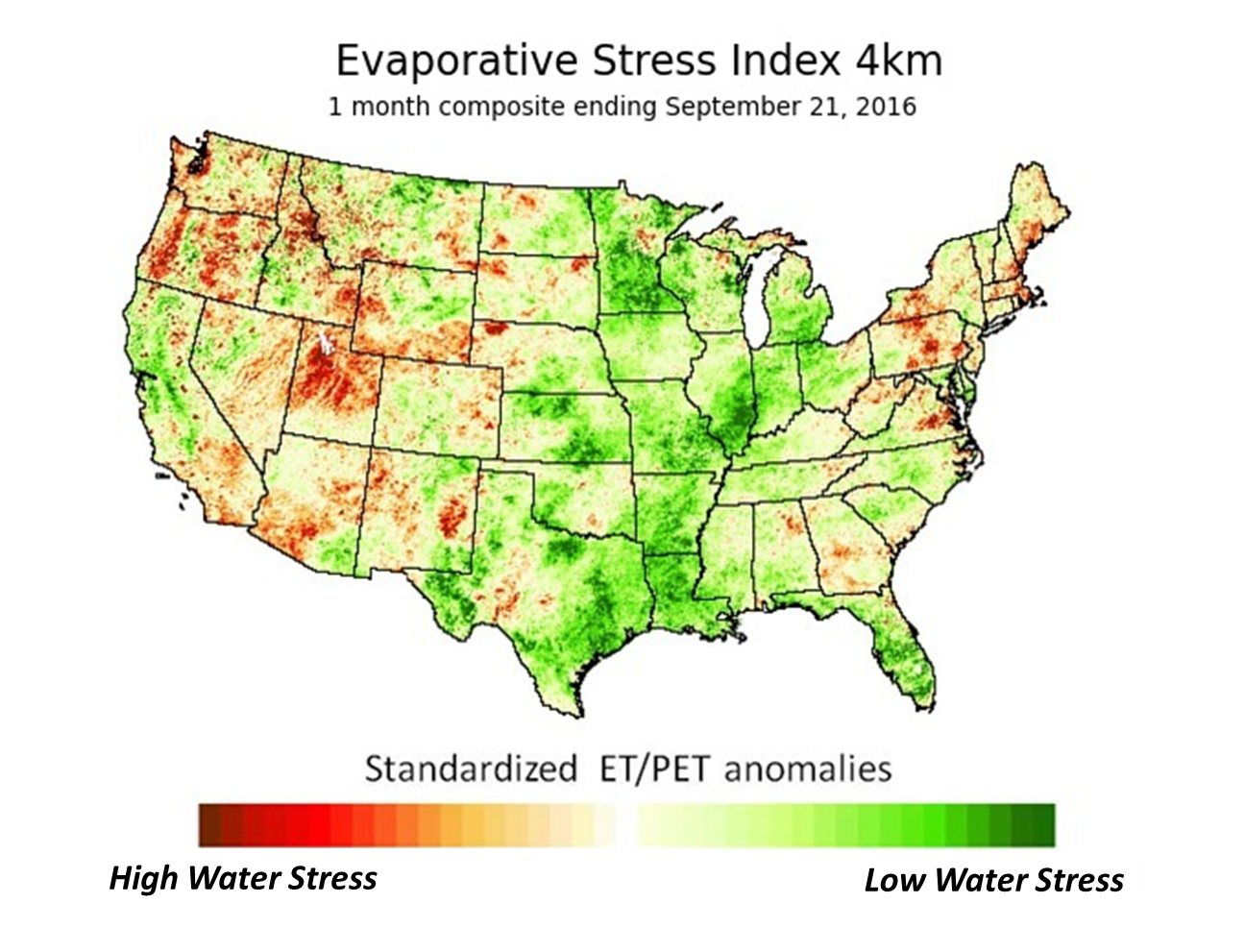

Otkin’s new early warning system is based on a plant moisture stress indicator called the Evaporative Stress Index (ESI). This system uses satellite observations from NOAA’s Geostationary Operational Environmental Satellite System to estimate water loss due to evaporation from the soil and transpiration from plants to the atmosphere.

When plants transpire, water moves from the roots to pores in the leaves and evaporates to the atmosphere. This process occurs more slowly when plants are stressed due to a lack of water. The beginnings of plant stress result in decreased transpiration. And because poor transpiration occurs before a visible decline in vegetation health, Otkin says the ESI can provide notice of flash drought development several weeks in advance.

NOAA released Otkin’s early warning system for flash droughts online in June 2016. With the ESI-based early warning system now operational, Otkin is focusing on understanding how to make the product more useful for agricultural communities, like the one where he grew up.

“Farmers and ranchers are not just a monolithic group of people,” Otkin says. Due to plant-specific characteristics like water requirements and heat tolerance, drought impacts on crops vary with plant type. Corn, soybeans, or wheat, for example, all react differently to droughts.

A continuing relationship with drought and weather

Otkin finds connections to science even in his hobbies. Now, when he isn’t spending time with his family and three-year-old daughter, he is quite the history buff–although he loves history because of science and his passion for the weather.

“Any kind of history is important,” says Otkin. “It’s like with weather and climate: it’s so important to be able to see what is happening today and put that in perspective with what happened in the past,” he says. “You can only do that by reading about the past.”

In the future, Otkin hopes to develop tools that are more specific to a given crop to provide more actionable information for farmers and ranchers.

Jason Otkin’s research is funded in part by the NOAA Climate Program Office’s Modeling, Analysis, Predictions, and Projections Program and Societal Applications Research Program.