Lamplugh Glacier, Glacier Bay National Park, Alaska, United States. Image by Diego Delso. Wikimedia Commons.

In a warming world, identifying snow and rainfall changes in locations around the world is a crucial effort due to the hydrological implications of such changes in addition to the surface albedo impacts. One such location is the last frontier, the state of Alaska. Although topography complicates the pattern of these changes in Alaska, the amplified warming and general increase in precipitation are already apparent in observational data. This begs the question, how will precipitation change with future warming? Snow is a high-impact environmental variable, with effects on transportation, infrastructure (e.g., snow loads on buildings), water supplies, vegetation, and air temperature.With snow cover having a profound effect on the economy and ecosystem, changes in snow cover are societally significant.

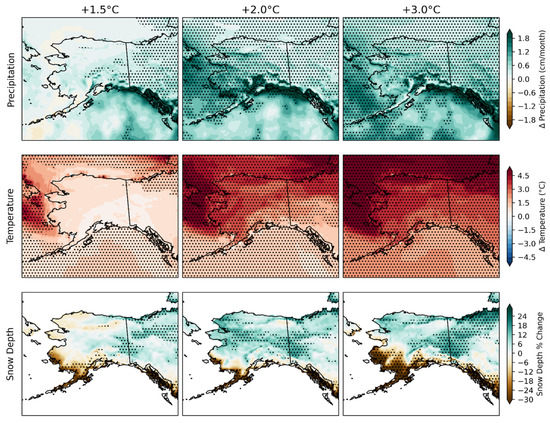

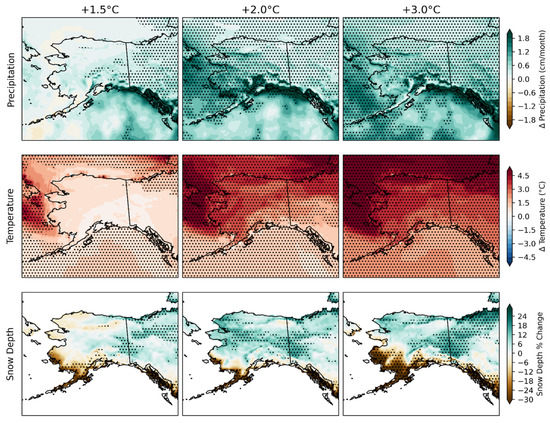

In a new Atmospheres article, authors Siiri Bigalke and John E. Walsh, use a high-resolution model to simulate changes in snow with global warming levels of 1.5 °C, 2.0 °C and 3.0 °C.

The study reveals that the amount of global warming strongly affects the change in winter snowfall over Alaska, with increases for both temperature and precipitation found under all three global warming scenarios. The increases become larger as the global warming increases. Future changes in snowfall are characterized by a north–south gradient over Alaska, with increased snowfall for northern Alaska. This gradient is likely because of heterogeneities introduced by the coastline and topography. . Temperature changes, on the other hand, show a strong land–sea contrast, with much stronger warming over the waters offshore of western Alaska where sea ice is lost, especially under the 2.0 °C and 3.0 °C global warming scenarios. It, therefore, appears that for both regions of Alaska, the threshold for a decrease in the high-elevation snowpack is a warming scenario between 2.0 °C and 3.0 °C. The change in snow depth would have important implications for surface hydrology, runoff, and hydropower generation.

Percentage changes in December–February precipitation, cm/month (upper row); temperature, °C (middle row) and snowfall, % change (bottom row) for stabilized global warmings of 1.5 °C (left column), 2.0 °C (middle column) and 3.0 °C (right column).

The authors note the results described here are a first look at the sensitivity of high-latitude snow cover to the level of global warming in a high-resolution global climate model. The results indicate that significant changes in snowfall in the Arctic and Alaska will be far less extensive if global warming is limited to 1.5 °C, the target of the Paris Agreement.

Funding for this project was provided in part by the NOAA Climate Program Office, MAPP program.

Read the full study here.