As our climate warms, some marine species are moving northward, diving deeper or shifting their distribution in search of cooler waters, affecting fisheries and fishing communities. But uncertainty regarding whether the benefits of proactively planning for these shifts outweigh the costs has remained a barrier for some to incorporate climate change impacts into ocean plans.

A new NOAA-funded and co-authored study says conservation of marine life migrating from warming ocean waters will be more effective and also protect commercial fisheries if plans are made now to cope with climate change. The study was recently published in the journal Science Advances.

“An impediment to planning for climate change is often the perception that large sacrifices must be made in the near-term,” said Lauren Rogers, study co-author and Fisheries Research Biologist with NOAA’s Alaska Fisheries Science Center. “We were excited to find that when it comes to ocean planning, we can design plans that will work now and in the future—that is, we can be proactive without sacrificing our current goals.”

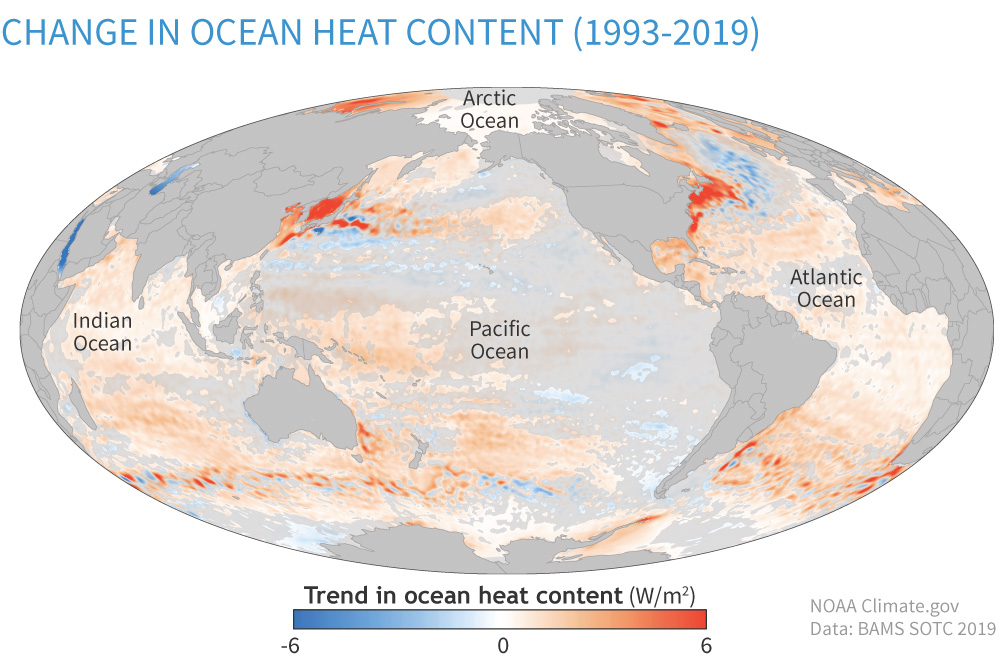

This map of heat content trends in the upper 700 meters (2,300 feet) of the world ocean shows where the oceans gained or lost heat between 1993 and 2019. Large parts of most ocean basins are gaining heat (orange)—and the global average trend is positive—but some areas have lost heat. Places with gray shading have trends that are not statistically significant. Map by NOAA Climate.gov, adapted from Figure 3 in the Oceans chapter of State of the Climate in 2019, based on data from John Lyman.

As the ocean becomes busier with shipping, energy development, fishing, conservation, recreation and other uses, planning efforts that set aside parts of the ocean for such uses have begun on all seven continents. However, these efforts typically do not plan ahead for the impacts of climate change despite establishing plans that can last for many decades.

With ocean waters warming, many commercially valuable fish species could shift their distribution toward colder water in the years ahead. Such movement is already underway – in some cases dramatically – substantially disrupting fisheries and exacerbating international fisheries conflicts.

“Sticking our heads in the sand doesn’t work,” said lead author Malin Pinsky, Rutgers University–New Brunswick associate professor supported by NOAA’s Climate Program Office. “Effective ocean planning that accounts for climate change will lead to better safeguards for marine fish and commercial fisheries with few tradeoffs.”

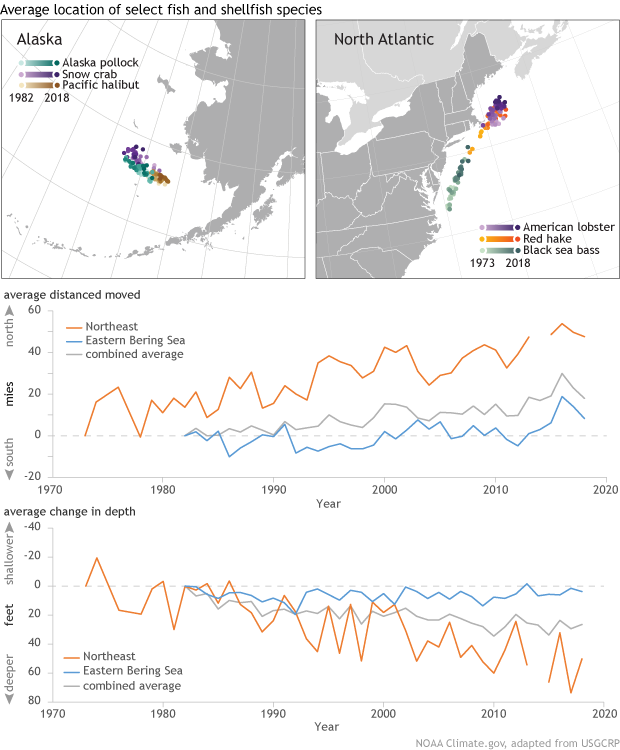

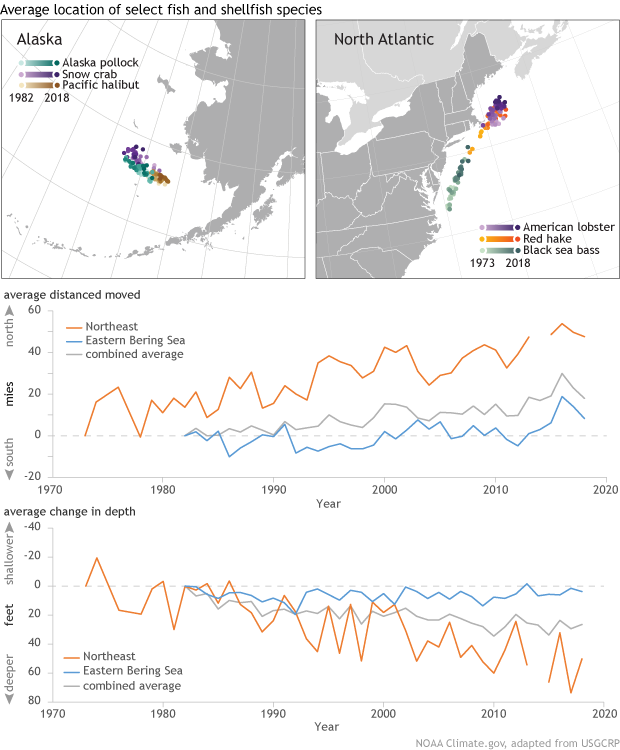

The maps show the annual geographic distribution for three species (Alaska pollock, snow crab, and Pacific halibut) in the eastern Bering Sea from 1982 to 2018 (left) and for three species (American lobster, red hake, and black sea bass) along the northeastern U.S. coast from 1973 to 2018 (right). The graphs show the annual change in latitude and depth of 140 marine species along the northeastern U.S. coast and in the eastern Bering Sea. Along the coasts, marine species are shifting northward or to deeper waters, and as smaller prey species relocate, predator species may follow. Graphic by NOAA Climate.gov, adapted from USGCRP.

The research team focused on the costs and benefits of planning ahead for the impacts of climate change on marine species. They simulated the ocean planning process in the United States and Canada for conservation zones, fishing zones and wind and wave energy development zones. Then they looked at nearly 12,000 different projections for where 736 species around North America will move during the rest of this century. They also looked at potential tradeoffs between meeting conservation and sustainable fishing goals now versus in 80 years.

“We were worried that planning ahead would require setting aside a lot more of the ocean for conservation or for fishing, but we found that was not the case,” Pinsky said. “Instead, fishing and conservation areas can be set up like hopscotch boxes so fish and other animals can shift from one box into another as they respond to climate change. We found that simple changes to ocean plans can make them much more robust to future changes. Planning ahead can help us avoid conflicts between, for example, fisheries and wind energy or conservation and fisheries.”

While the study focused on long-term changes, many fisheries decisions are focused on near-term changes – one to a few years ahead, Pinsky said. So the scientists are now testing whether they can forecast near-term shifts in where species are found so fisheries can adapt more easily to species on the move.

Though climate change will severely disrupt many human activities and “complete climate-proofing is impossible, proactively planning for long-term ocean change across a wide range of sectors is likely to provide substantial benefits,” the study says.

This study was funded in part by the NOAA Climate Program Office Coastal and Ocean Climate Applications program and the NOAA Fisheries Office of Science and Technology. Scientists at Stanford University, East Carolina University, and University of Bern also contributed to the study.

This story was adapted from a Rutgers University-New Brunswick press release.