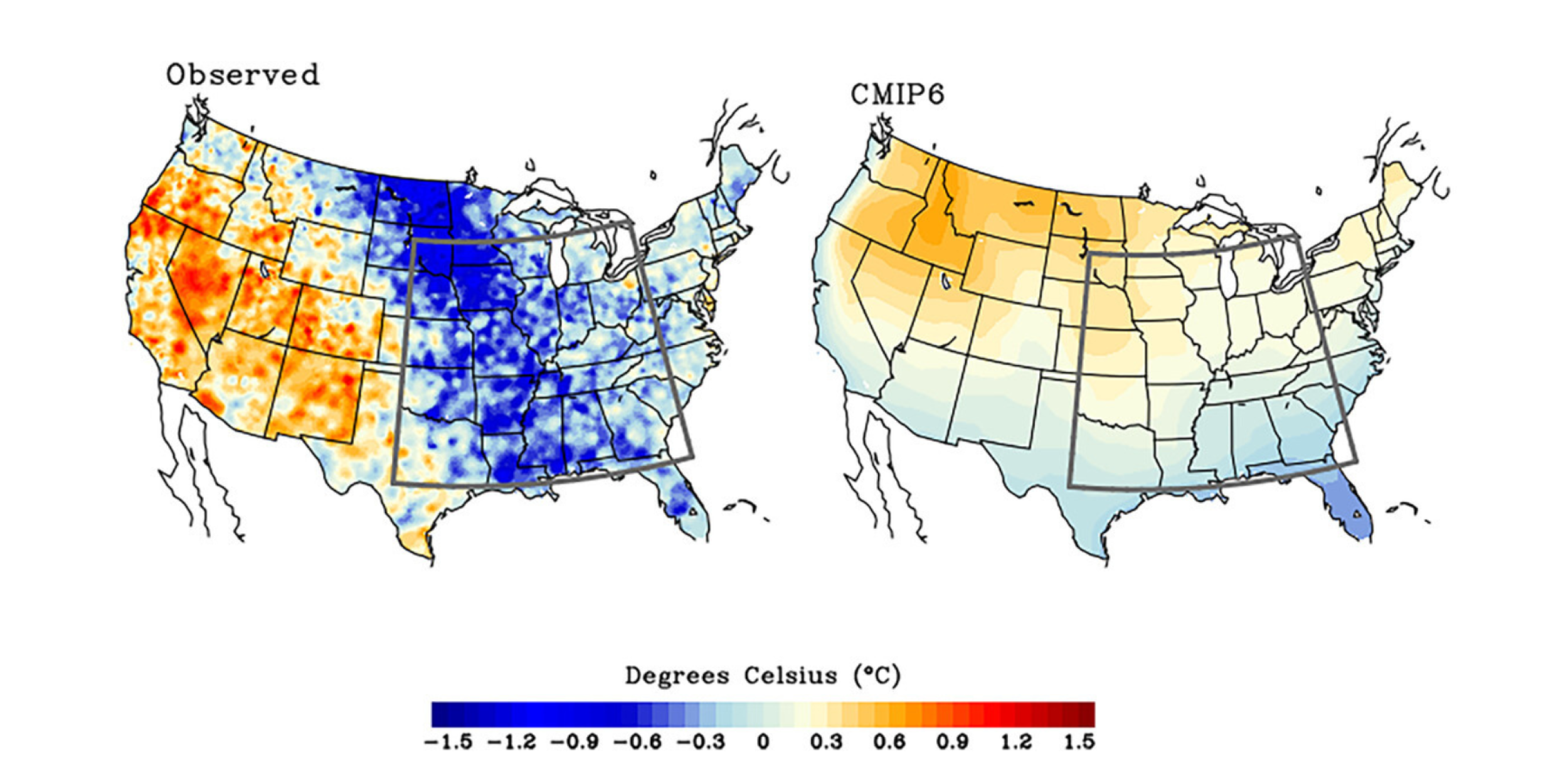

Amongst rising temperatures in the Western and Eastern United States, there has been a cooling trend in summer daytime temperatures over the central United States since the mid-twentieth century. This cooling trend was thought to have formed from internal climate variability and would likely disappear. However, the “Warming Hole” has prevailed for decades despite global warming. Scientists are now reexamining this phenomenon, which may extend beyond natural variability to include anthropogenic influences such as aerosol-induced cooling, hydrologic cycle intensification due to greenhouse gas emissions, and land use changes.

In a new Journal of Climate, authors Jon Eischeid, Martin Hoerling, X.-W. Quan, Arun Kumar, Joseph Barsugli, Zachary Labe, Kenneth Kunkel, Carl Schreck III, David Easterling, T. Zhang, J. Uehling, and X. Zhang use a variety of climate model experiments with large ensembles to better understand the role of external radiative forcing and to diagnose the possibility that internal variability alone could account for the particular pattern of twenty-first-century U.S. summertime warming.

The research reveals that the warming hole’s persistence is consistent with unusually high summertime rainfall over the region during the first decades of the twenty-first century. Comparative analysis of large ensembles from four different climate models demonstrates that rainfall trends since the mid-twentieth century can arise via internal atmospheric variability alone, which induces warming-hole-like patterns over the central United States. In addition, atmosphere-only model experiments reveal that observed sea surface temperature changes since the mid-twentieth century have also favored central U.S cool/wet conditions during the early twenty-first century. Researchers argue that the persistence of this pattern of increased rainfall/lower temperatures is likely due to near-equal contributions of external forcing (climate change) and internal climate variability.

The findings of ocean and atmosphere drivers as a significant factor in causing the ongoing warming hole contrast with an alternate view that emphasizes the leading role of changing agricultural practices. Evidence in this study cast doubt on arguments for a leading role played by land use/land cover change, including management practices linked to agricultural intensification. It was also noted that the time series of summer rainfall over the broader central United States—remarkable for its dramatic jump in the recent decade—is inconsistent with notions of a steady increase in cropland primary production. Uncertainty remains on how land use/land cover change impacts climate (contrast Alter et al. with Chen and Dirmeyer). It is plausible that the most important mechanism for the warming hole identified herein is inconsistent with mechanisms linked to land use change, at least for the broader central U.S. region considered herein.

Researchers are now asking about the probability of particularly hot summertime central U.S. temperatures, an occurrence largely lacking in recent decades. For instance, what is the risk that the hottest summer on record for the central United States (1936) may be eclipsed in the coming years? The analysis reveals little change in the probability of such an event in simulations during 2000–30, with the odds generally at or below a 1% risk. By contrast, SPEAR indicates a 10% risk already by 2020 and a nearly 30% risk by 2030.

Funding for this project was partly provided by the MAPP program.

For more information, contact Courtney Byrd.