The article continues a series of interviews with NOAA Climate Program Office (CPO) employees and CPO-funded scientists in celebration of Women’s History Month.

Dr. Xin Lan is a carbon cycle scientist with NOAA Global Monitoring Laboratory (GML) through the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences (CIRES) of University of Colorado Boulder. At GML, Dr. Lan is the lead scientist responsible for NOAA’s Global Cooperative Greenhouse Gas Measurement Program (part of the Global Greenhouse Gas Reference Network). NOAA monitors main GHGs: carbon dioxide, methane, nitrous oxide, and sulfur hexafluoride, and other ozone depleting substances.

Additionally, as a scientist funded by CPO’s Atmospheric Chemistry, Carbon Cycle, and Climate Program, Dr. Lan’s research on the global methane budget helps improve our knowledge of climate feedback on natural emissions.

Dr. Lan has devoted her career to understanding carbon cycle feedback, communicating the science, and communicating the urgency of taking actions to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Our conversation follows:

Can you tell me about your journey to becoming a scientist and any early influences that inspired your career choice?

We started to hear about air pollution on the news when I was in college in China. While my major of study was in meteorology, I also found chemistry interesting. We had atmospheric chemistry classes and research projects on air pollution and those subjects came naturally to me. I decided to study air pollution because it combined the many fields that interest me including meteorology, air transport, chemistry, and atmospheric gas reactions.

When did you come to the U.S.? Was it for school, work, family?

I always wanted to explore and to find opportunities to do good science studies. For atmospheric science studies in particular, I knew universities in the U.S. had good reputations. So, after my bachelor’s degree, I went straight into a PhD program at the University of Houston in 2010.

After getting my PhD in 2014, I joined NOAA GML in August 2015 as a postdoc through a fellowship from the National Research Council. I officially joined CIRES in December 2016 and have stayed working with NOAA GML.

What sparked your interest in studying greenhouse gases?

My PhD study was on air pollutants and short lived trace gases and I also got an opportunity to work on the first set of U.S. study investigating oil and gas methane leaks in Texas. I found it very interesting and wanted to learn more about the universal impact that long-lived greenhouse gases have on the global systems.

What are some of the challenges you face in studying greenhouse gases, both scientifically and practically?

Scientifically, the challenge is that we have very limited measurements to understand the global carbon cycle well. I have a unique role to speak to this, because I am the measurement Principal Investigator responsible for the largest number of greenhouse gas measurement sites in the world. Everything is linked together, but the measurements are very sparse for us to be able to decide what each contributor is doing in the carbon cycle. The sparse measurements lead to large uncertainty in predicting carbon cycle feedback to changing climate.

How do you communicate your research findings to the public, policymakers, and other stakeholders?

A lot of the time, if I have an interesting paper, I reach out to NOAA Comms to develop a story about the findings. Since I’m responsible for the global greenhouse gas trends, I get a lot of public inquiry emails on a weekly basis and I try to respond to them as much as I can, but I also work with NOAA Comms to send out an annual press release on the trends.

I actively participate in writing reports like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change assessments as I am a coauthor of the Global Carbon and other Biogeochemical Cycles and Feedbacks chapter. I also participate in other stakeholder meetings.

What gives you hope with regard to greenhouse gas science, your field in NOAA, or in general?

Becoming a mother was a turning point for me. Before I had my son, the topic of greenhouse gases was fascinating, but now, my concern about his future and other future generations is so obvious to me. If I lost hope, that means I lost hope in my son’s generation and in our future. I choose to remain hopeful in science even when I communicate its urgency. Hopefully, more younger generations will consider becoming scientists studying greenhouse gases and the carbon cycle.

What is your communications strategy for the carbon cycle?

My approach is to explain the carbon cycle in a fundamental way so that people understand why we are seeing these particular features in our measurements, and how greenhouse gases play a role in global warming. For carbon dioxide, I explain why emissions from human activities drive the trend. For methane, I explain why human-caused emissions can also cause climate feedback to increase greenhouse gas emissions from natural systems.

I also communicate that it is not too late for action and many things can still be done to prevent bad things from happening. Hopefully, actions will be taken quickly without waiting for the worst-case scenario.

What is something you wish more people knew about carbon cycle science?

The first thing people need to understand is that everything in the Earth’s systems is interconnected. It can be difficult to comprehend that. For example, if there’s a leak of methane emissions from a U.S. oil and gas operation, there is a possibility that we will see signals from the Arctic to Antarctica, because everything is connected via air transport. People need to understand that their lifestyles and behavior have downstream impacts on the ecosystem which is why there is urgency to change some of our behaviors to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Even though some aspects of the carbon cycle are not yet well known, we know with certainty that human-caused greenhouse gas emissions are causing climate change.

We already have enough knowledge to act to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

In your opinion, what role do individuals play in reducing greenhouse gas emissions, and what lifestyle changes do you recommend?

There are many things we can do. I believe individuals must be willing to change how they consume energy. That’s the most important thing. What gets us in trouble, mostly, is the fossil fuel usage and release of carbon dioxide through fossil fuel usage. It links to every aspect of how we use energy.

To change how you consume energy, first, be aware of it and think about how you can reduce your energy use, or carbon footprint, and how to use other renewable energies to substitute some of the energy you need to use. Use public transportation if possible.

From a production point of view, do we really need to produce a huge package for some products that are used once and immediately go to landfill? We need to think about the lifecycle of particular products we’re using right now and shy away from single-use products. Recycle and compost.

For reducing methane emissions, another thing that will be helpful in addition to thinking about composting is our red meat consumption. A significantly large amount of methane emissions is associated with livestock cultivation. We also need to think about equity. There are some countries that have very low capital greenhouse gas emissions and we need to allow those to grow a little bit because we don’t want to further deteriorate living standards that are already in critical conditions.

So there’s a lot to think about. There are immediate steps and longer-term steps that have implications in society.

What is a moment from your career you feel proud of?

A very enjoyable moment as a scientist is when I go to a science conference and people come up to me and say they read my paper, agree with my findings, and then we start having a very good discussion about it.

Also, related to my experience talking with media climate reporters, first, I often talk with a reporter for two to three hours because they are genuinely interested in understanding the global carbon cycle and greenhouse gases. Second, seeing the end piece of an article and realizing they accurately delivered my message makes me feel really good. I know that through their message, what I said reached a large audience.

Can you discuss any recent breakthroughs or developments in the field of greenhouse gas research that you find particularly exciting?

I think the scientific community can agree upon the importance of greenhouse gas measurements right now and also recognize the need to expand these measurements.

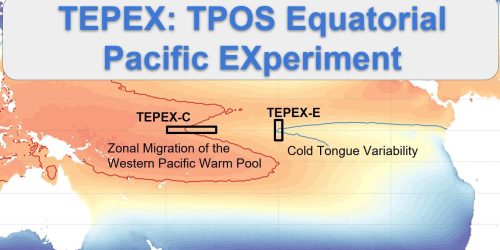

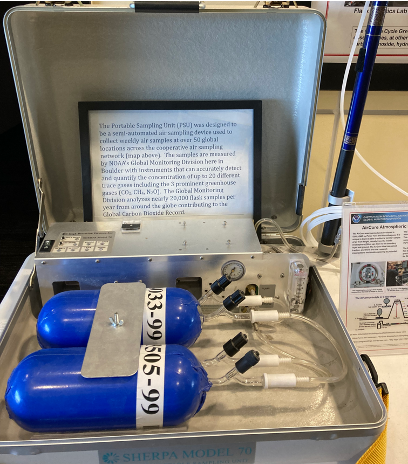

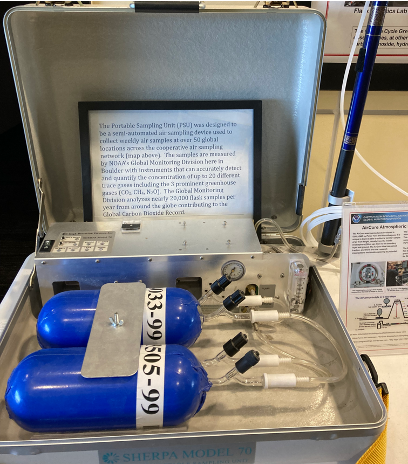

My group has operated a very unique, globally distributed, measurement network since the 1960s. We ask people to take air samples and send them back to us for analysis. We now analyze around 18,000 flask-air samples from approximately 75 locations around the world each year, but we need more of these measurements.

I hope the next breakthrough will be a large expansion of greenhouse gas measurements to help us understand the science better and encourage more participation from countries that haven’t given much thought about monitoring greenhouse gases. Increasing society’s ability to track greenhouse gas emissions can also help determine if any reduction actions/policies are effective.

What are some misconceptions or stereotypes about women in science that you would like to challenge?

When I grew up, I was told that girls cannot do as well in science and math as boys, and I don’t agree with that. I challenge that by action. I was a top student in math, physics, and chemistry. Now I’ve been a scientist for quite a few years.

To be a successful scientist, you need the ability to have critical thinking skills and work in a large collaborative effort, especially for greenhouse gas. Both boys and girls can be good at that. There’s no clear gender separation in what we are good at doing.

In your opinion, what can be done to encourage more girls and women to pursue careers in STEM fields?

First of all, we need to fight some of the stereotypes that we discussed earlier and that I personally think are not true. It would be helpful for school teachers to engage female scientists in outreach activities and provide more opportunities for girls to be exposed to science at a young age so they can learn what a career as a scientist in general and as a female scientist looks like.

For the young women looking to study greenhouse gases, what is your greatest piece of advice?

I think it’s a great way for you to make a positive impact on your life, the lives of others, and the whole Earth environment.

If you are currently studying sciences, don’t give up. We all get stuck at a certain point. If you are stuck with math and science subjects in school, reach out for help.

Even if you’re not good at science and math, take a step back and re-evaluate. You can still be good at communication to help link the scientist to the public. You can be good at visual art to show the impacts of greenhouse gas and global warming and raise people’s awareness. You can help find solutions. There are many things you can do to contribute to making positive impacts on mitigating or limiting the global warming crisis.

What do you hope people will take away from Women’s History Month celebrations and discussions?

I really feel that Women’s History Month is a special time to celebrate and reflect. We’re celebrating the huge contributions women have made to many areas of life. For me, I pay particular attention to the women who paved the road for women scientists.

Also, I think it’s a time for reflection on where we need to improve going forward. I don’t think we need to focus on obstacles of the past. I hope we can encourage more girls to do science and encourage them to think about how to make their future career impactful and beneficial for society.