Growing up in São Paulo, Brazil, Dr. Suzana Camargo was uncertain about her professional future. She did, however, know one thing for sure: she had a keen interest in physics. She credits her father and grandfather, both engineers, for inheriting that passion. She earned bachelor’s and master’s degrees in physics at the University of Sǎo Paulo, then completed her PhD and postdoctoral research in Germany, at the Technical University of Munich and the Max-Planck Institute for Plasma Physics, respectively.

Her career shifted in 1999, when she accepted a position at Columbia University’s International Research Institute for Climate and Society (IRI), which was originally established through a cooperative agreement between Columbia and NOAA’s Climate Program Office. She admits that, at first, the transition between physics and climate science was hard. But it never held her back.

“I had a lot to learn and didn’t know the jargons used in the field,” Camargo says. “Once I started to make the connections between the two fields, things became easier. During my PhD and postdoc, my research focused on turbulence in plasma physics–studying turbulence in fluids and solid background in fluid dynamics–which was very important for the transition to atmospheric sciences, as both these topics are fundamental for the field.”

Her star has risen each year in the climate world thanks to her talent and determination. She joined the prestigious Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory in 2007, where she currently works.

“Lamont is a wonderful place to work,” Camargo explains. “There are scientists doing field work in Antarctica, others taking drones to film erupting volcanoes, and some developing new modeling techniques. It’s a very interesting environment to work in. With the creation of the Climate School, I’m certain there will be new and interesting discoveries and solutions for the future coming from Lamont and Columbia University.”

Camargo is a prolific writer and researcher on tropical cyclones and other climate topics; many of her research publications are widely cited by peer scientists. NOAA Climate Program Office’s Modeling, Analysis, Predictions, and Projections (MAPP) Program has funded some of her work. For the last few years, she has been working in risk, trying to build models to understand tropical cyclones because historic models and figures provide insufficient data.

The field of tropical cyclone research is a very active, dynamic area for climate scientists today. Camargo points to technological progress in the last 20 years that have improved hurricane data accessibility and improved modeling as bigger and better computers facilitate simulations forecasting. On the other hand, she notes that scientists still don’t know how to predict the number of tropical cycles that will form each season. There aren’t complete theories; everything is a projection and based on models, which poses stark challenges for climate researchers.

Camargo also conducts significant media outreach, including interviews with major outlets such as The Washington Post, The New York Times, Bloomberg, and BBC. She indicates that this outreach is an integral part of her job. When members of the media inquire about her research, she responds so they understand the importance of her scientific findings.

“Journalists mostly contact me when there’s a major weather event in the forecast,” Camargo states. “Journalists want to understand more about hurricanes and their impact on society, and it’s important to keep the public informed.”

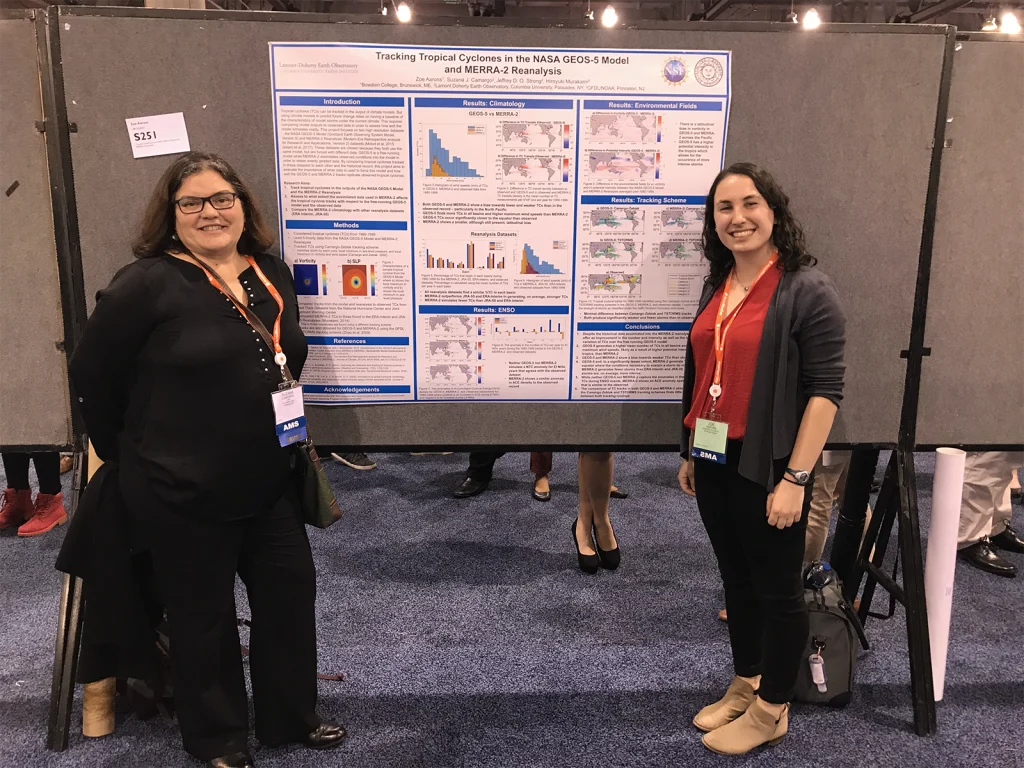

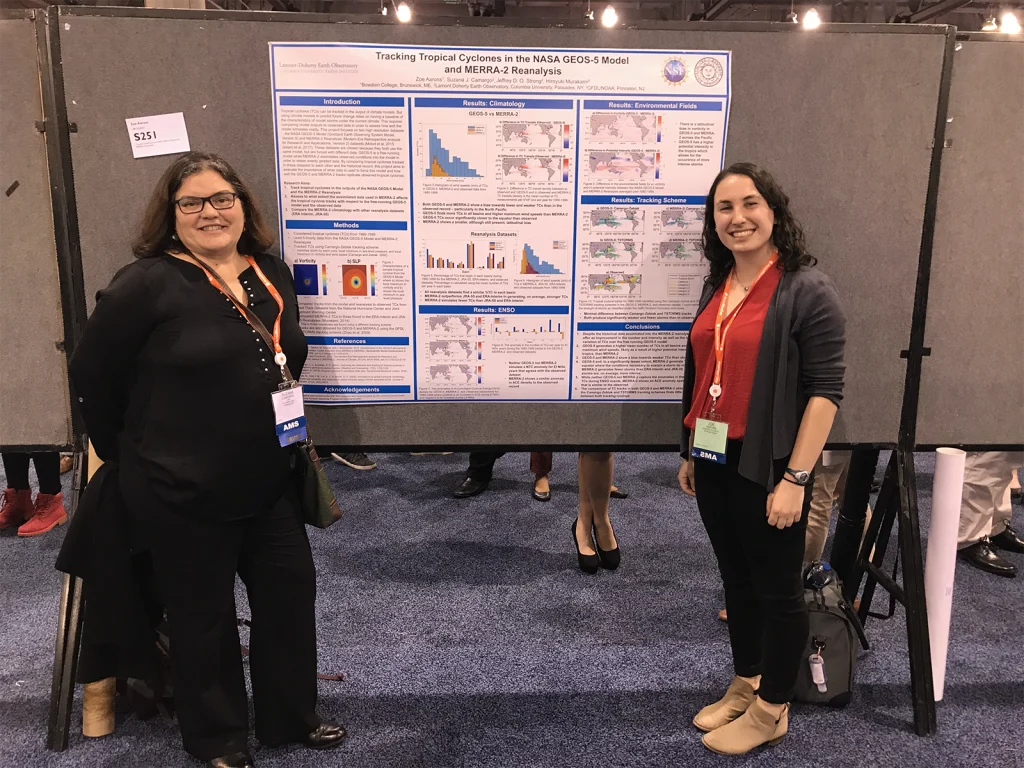

Finally, she makes mentorship of students and early career scientists a major priority.

“Mentoring is one of the highlights of my job,” Camargo notes. “It’s a pleasure to interact with them and then follow their growth, as they learn. I’ve learned a lot from interacting with my mentees and their interests have led the research to unexpected places. It makes me proud to see my previous mentees become successful scientists and make the transition from mentees to colleagues.”

As a Latina, Camargo expresses the importance of building a network of colleagues and mentors that can give you advice. During her education in Brazil, she enjoyed many friendships with fellow physics students–friendships that have continued to support her through her professional life.

Additionally, she works dilligently to improve diversity and inclusion in climate science. She was a member of the Diversity Committee at Columbia’s Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences (DEES) from January to September 2020, but she admits that diversity is a work in progress but the entire field is looking to improve it.

“There’s not one clear cut solution,” Camargo asserts. “ There are a lot of things that we should and shouldn’t be doing, but a combination of approaches from many levels that begin in society should help our efforts.”

As our campaign to understand climate change continues, Camargo knows there is hope for a better future. There isn’t one solution to this issue, she says.

“We have to do everything. And it starts with widespread knowledge and educating the public.”

All photos courtesy of Dr. Camargo.