In honor of Women’s History Month, NOAA is highlighting a few of its female scientists and funded researchers who are making significant strides in the climate sciences and other science fields. The following interview is with Dr. Lucy Hutyra, an Associate Professor in the Department of Earth and Environment at Boston University. Her research is funded, in part, by NOAA Climate Program Office’s Atmospheric Chemistry, Carbon Cycle and Climate (AC4) Program. She studies exchange processes between the atmosphere and biosphere, focusing on the terrestrial carbon cycle and the impact humans have on it.

Dr. Lucy Hutyra with her Boston, Massachusetts field site behind her. Photo courtesy of Dr. Lucy Hutyra.

When did you first become interested in science and ecology?

I didn’t have a lifelong goal of being a scientist or professor. I was the first in my family to attend college. My parents were immigrants and they didn’t have a lot of experience or guidance to offer, other than advising, “Education is good so get one.” They strongly pushed education, particularly for me, the only girl in the family. However, they didn’t really push me in a specific direction.

For my undergraduate and master’s degrees, I focused on forest ecology because I liked to be outside and it was fun. I was probably about 23 or 24 years old when I started to focus on the carbon cycle and realized I might want a career in science. I was working as a research technician at a Harvard University lab, doing a lot of field work to understand the carbon exchange in the Harvard Forest and analyzing the data. During my three years as a technician, I also worked in forests in Canada, Brazil, and Bhutan. It was an incredible experience to work in such completely different ecosystems — from tropical to temperate to boreal — and do different kinds of work, from atmospheric measurements on a tower to digging soil pits to understand how much the soils were contributing to the CO₂ that the tower was seeing. When I was doing that work, I had no idea what I actually wanted to do long-term. I was just enjoying the moment. For the first time in my life, I was also shaping what the next steps of the experiment were going to be. I started to feel ownership over the project. That sense of discovery and innovation took hold. And then I decided to pursue a PhD and it went from there. It just sort of happened. I found a passion.

Your PhD thesis at Harvard focused on Carbon and Water Exchange in Amazon rainforests. How did your experience working in the Amazon rainforests shape your interests?

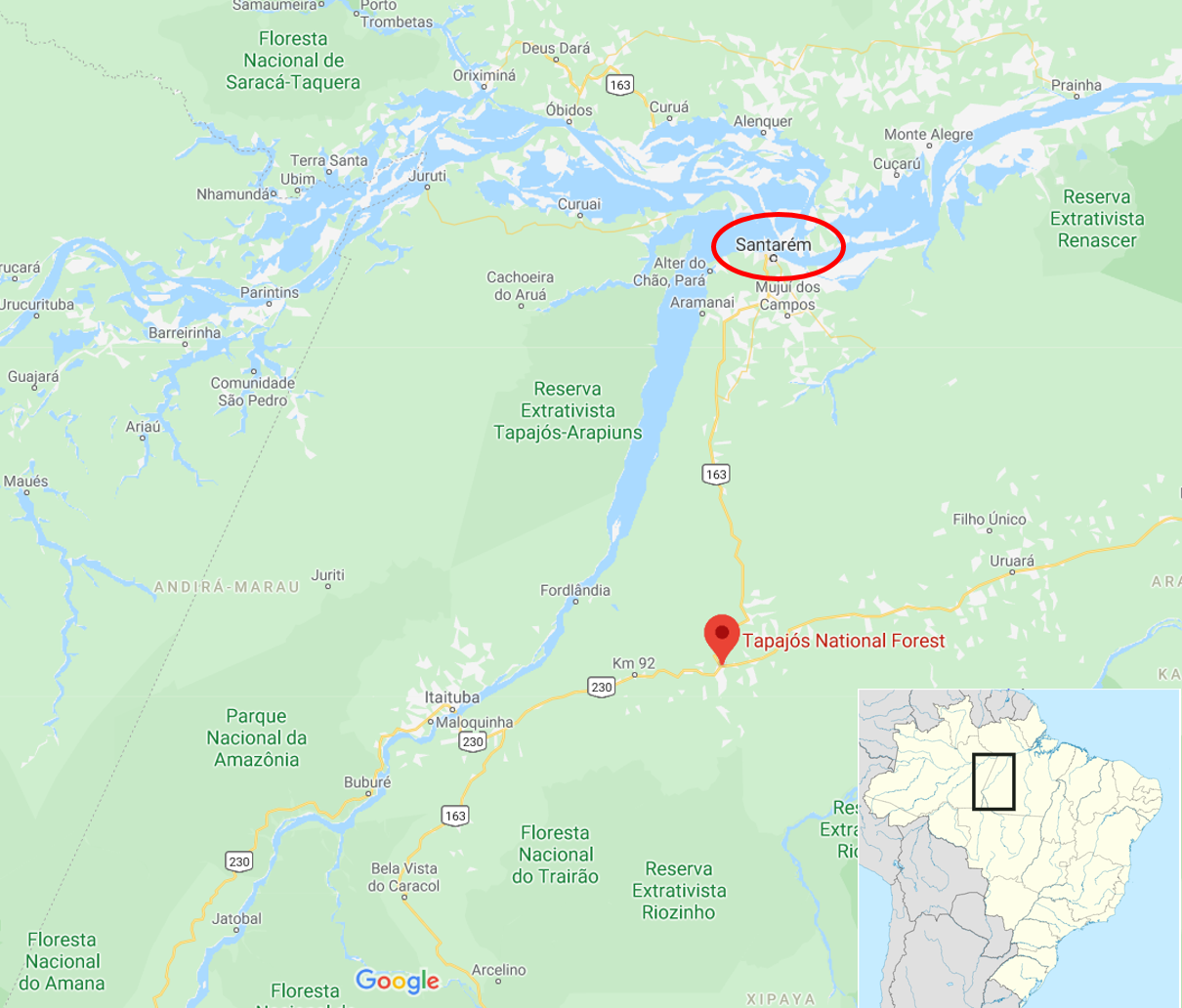

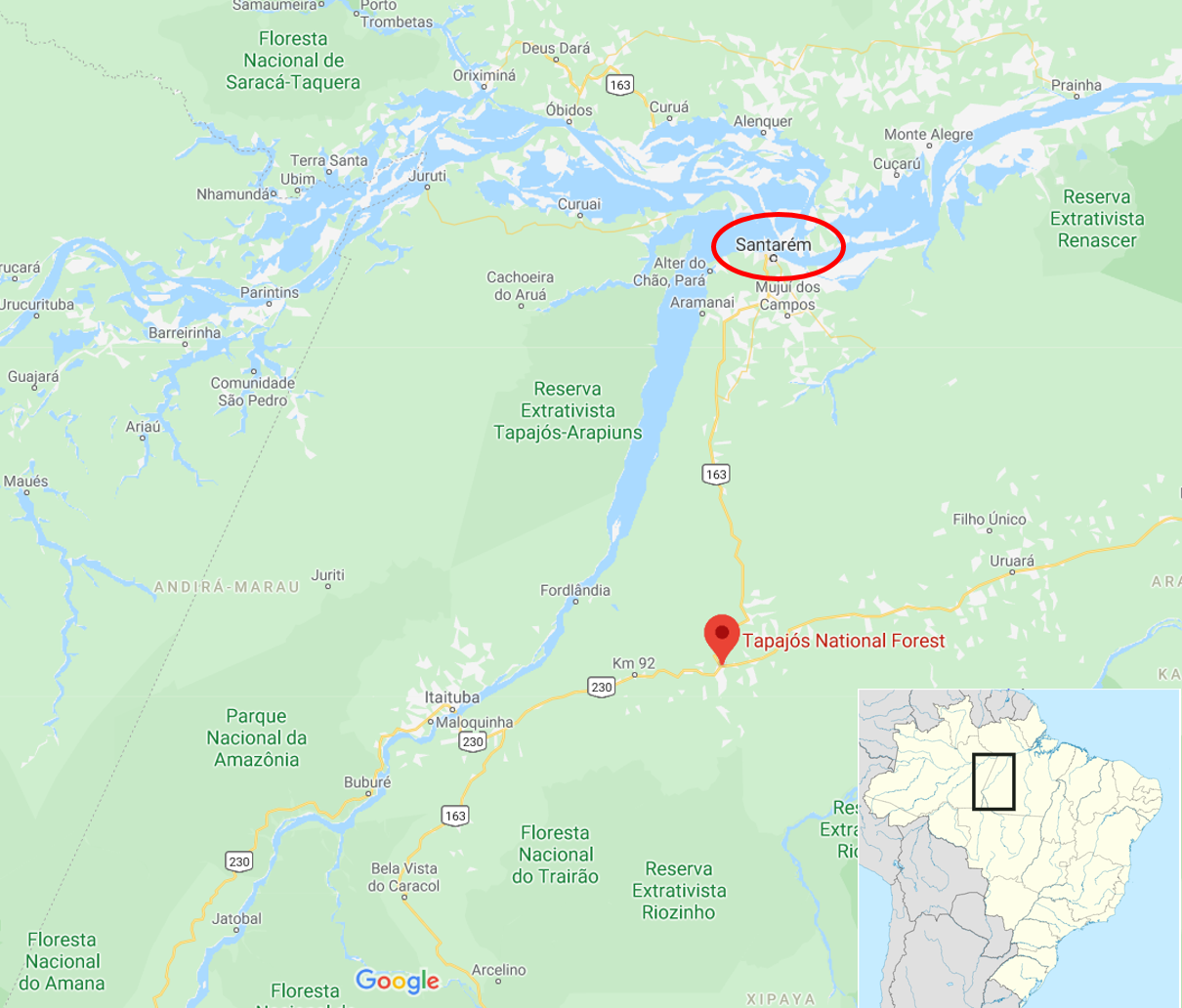

During my PhD, I worked in Brazil’s Tapajós National Forest, near a town called Santarém, which is the third-largest city in the Brazilian Amazon. That area was rapidly developing. Forests were being replaced with soybean fields and massive industrial scale agriculture was coming. Santarém is at the confluence of two major rivers, which makes for very easy transport of crops.

I got to watch the landscape around our experimental forest completely transform, and that experience actually shaped a lot of what I do now. Since then, a lot of my work has become local. I’m thinking about greenhouse gases in cities, rather than in remote forest locations. It was watching the transformations in the Amazon landscapes that really pushed me to work at the local scale. Not that the Amazon isn’t important, but I wanted to feel like my science was having an impact on the sustainability and viability of the ecosystem where I live.

Map showing the location of Brazil’s Tapajós National Forest near Santarém. Source: Google Maps.

As you mentioned, a lot of your work now at Boston University focuses on urban greenhouse gases. What do you enjoy most about working in this space?

I’m very passionate about doing science that makes a difference. Over 70% of greenhouse gas emissions are concentrated in cities, so the policies that are enacted in cities make a huge difference to our atmospheric greenhouse gas burden. My lab’s research focuses on studying whether and how the policies that cities and states are putting forth for reducing greenhouse gas emissions are working. Are the pledges, for example, of an 80% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by the year 2040 being manifested in the atmosphere? We’ve worked for the last 10 years to figure out how to measure that — the gases in the atmosphere, in the city, in the areas surrounding the city — and think about where the gases are coming from and how air is transported. We’ve also learned about the role of the biosphere in cities and what nature-based solutions or urban greening initiatives might actually mean for a city, its climate action plan, and the air quality and the atmospheric composition in cities.

We ended up spending a tremendous amount of energy on building urban fossil fuel emissions inventories which didn’t exist. It’s been really fascinating to realize what we know and what we don’t know about emissions. For a long time, the atmospheric community assumed that emissions were perfectly known, but it turns out they are not. It’s an incredibly exciting space to be working in. I think we’ve influenced local and national public policy with our scientific observations and insights.

Your project CO₂ Urban Synthesis and Analysis (CO₂-USA), funded by CPO’s AC4 Program, has developed urban emissions inventories. What is the impact of this project?

Across the United States, there are a number of cities that have atmospheric measurement networks for CO₂, methane, and some additional gases. The cities involved in CO₂-USA — for example, San Francisco, Los Angeles, Salt Lake City, Indianapolis, District of Columbia, Baltimore, Boston, and Portland, Oregon — are very different in terms of what greenhouse gas policies are being enacted, what their emissions profile looks like, and what the ecosystem in and surrounding them looks like. So, we are trying to bring cities around the United States together to do a comparative analysis of greenhouse gas emissions trends, patterns, and uncertainties. We’ve built a harmonized emissions dataset so that we can analyze these atmospheric observations with consistent emissions estimates in terms of what we think is coming from the ground compared with what we are measuring in the air.

The transportation emissions product that we built for CO₂-USA was picked up by the media. People around the country could look at what the trends in emissions were in cities across the United States. That dataset was downloaded over 20,000 times. It was a reach I never imagined was possible. People that know nothing about atmospheric sciences or greenhouse gases could see these trends in their neighborhood and what their behavior in the transportation sector really translated to.

The most important thing we are doing in CO₂-USA is bringing the scientists as well as the stakeholders from these cities together. In many cases, the people who are making policy decisions about climate action and sustainability had no idea that there were these massive networks of observations present in their city that are relevant to the policies they are trying to set. Through the CO₂-USA project, we have tried to synthesize the science and individual insights from the cities and merge it with the policy understanding. In many cases there’s immediate utility for those insights.

Can you share some insights you’ve learned so far about urban greening initiatives from your research?

Recently, we have been finding an acceleration in the cycling of carbon dioxide by ecosystems in cities. We have found that urban trees are much more efficient at growing and capturing carbon than their country cousins. In fact, they are about 4 times as efficient if you control for size and species. This means that these urban trees are going to have a very large influence on atmospheric CO₂. Plants in cities are growing in an environment, in terms of temperature and CO₂, that’s more favorable. Urban trees have a longer growing season and they are being beautifully fertilized by all of those fossil fuel emissions. There are some negatives associated with those emissions — ozone and other pollutants that could affect the tree — but it seems that the benefits are outweighing them. If we assume that a plant in a city performs as our standard textbook models predict, we are going to underestimate how much CO₂ will be taken up. That really has turned some of my thinking on its head.

Last year, at the American Geophysical Union’s Fall Meeting, renowned environmental scientist and former NOAA Administrator, Dr. Jane Lubchenco, called for “a renewed social contract for science.” She asked the scientific community to consider “our obligations as scientists [and] our responsibilities to society, to each other, to future generations.” What responsibilities do scientists have to society?

We have an obligation to do more than basic, fundamental scientific research that we publish in disciplinary journals. Society needs our science today and tomorrow to inform policy and make sound decisions. My interactions with the stakeholder and the policy communities has inspired and motivated my work. They have research needs and are really important and interesting. Now is the time for solution-oriented science. That may mean we have to leave the comfort of the lab and engage in different kinds of challenges. It takes determination and a plan to have your science reach the right people to solve problems. Odds are, they are not reading our disciplinary journals.

You’ve accomplished a lot in your career. Did you have any significant mentors?

Through connections and suggestions from advisors and professors in undergrad and graduate school, I applied for a position with Professor Steve Wofsy at Harvard. I was completely unqualified, but he hired me. Steve proved to be the most amazing mentor that any student could ask for. He offered opinions without telling me what to do. He shaped the rest of my life. I still call him up regularly for advice. I’ve tried to mimic some of his approaches to mentorship with my own students.

There was a female postdoc when I was at Harvard who ended up having two children during her postdoc years there. At the time, Harvard didn’t have a postdoc maternity policy. I watched Steve’s audacity, as he pushed university administration to create one. And he helped get one. Today, my first female postdoc to have a baby is due next month. So, I looked into what my university’s maternity leave policy was and I wanted more. Following Steve’s lead, I had the audacity to go to my vice president for research and ask for change. And my university is now working behind the scenes to improve the postdoc maternity leave policy. If I succeed in this, it will be one of my biggest accomplishments.

As a mentor now yourself, what advice would you give to your younger self or to a woman just starting out in her career?

Don’t accept “No.” It took me a long time to realize that I didn’t have to accept “No” as an answer. Sometimes, when you actually appeal a decision, you can reverse it. You have to pick your battles, but know that you don’t have to accept the status quo in policies or in manuscript reviews. I now feel empowered to appeal decisions.

What challenges have you faced as a woman in a male-dominated field?

Just like practically every woman I know, I still suffer from imposter syndrome. Imposter syndrome is unfortunate, but it is also normal. There were things that I think I got because they needed a woman on a committee and they couldn’t find one so they asked me. I would be the only woman on a committee and I would think I didn’t belong there because they were trying to get some kind of gender balance and they achieved it with my help. Maybe that was true, but once I joined the committee, my voice was equal to everybody else’s. Ultimately, I changed some of the committee’s directions and policies. We have to know where the limits of our knowledge are, but we also have to acknowledge that we’ve gotten to where we are for a reason. We need to stop beating ourselves up.

I think my biggest challenge as a woman came when I had a baby. My university had generous faculty maternity leave policies, but that was the hardest period of my career. It wasn’t hard just during the period of maternity leave. The challenges extended for years. The single biggest challenge I had during that time was how to navigate travel. I could do everything in the office, but a lot of building a career, advocating for research, and highlighting research findings requires that you travel. I curtailed my travel for 5 years because it was just too hard until my son went to kindergarten. My university didn’t give me a budget to take a nanny with me when I traveled. So, in those years I was limited. And those years are really important in shaping a career because they establish your reputation and career. They just happen to coincide with many women’s prime childbearing years.

Does your son like trees too?

My son loves trees and being outside. I have a really cool kid. He is 7 years old now. He is adventurous. We go hiking, biking, and swimming. I keep trying to get him to think about something other than geology, but he has built a rock museum in his room which has thousands of specimens. It’s really something. He has multiple microscopes and loves rocks. He’s also just starting to learn about climate change now. At the women’s science march we made posters for him and his friends about air pollution. The passion with which he advocates for the environment is amazing.